A desktop power supply is, in my opinion, the single most important tool for an electronics engineer to have (after a multimeter of course.) As such, building my own from an old laptop power supply was an essential step in my ECE journey, and I learned a lot about the basics of electronics design along the way.

Materials

Required

- Laptop power supply (~65 watts)

- 5 amp DC-DC adjustable buck converter

- Voltage + current display

- Banana plugs

- 10kΩ potentiometer

- Power Switch

- 3D Printer + filament

Additional Hardware

- 4x M3x8mm machine screws

- 4x M3 heated inserts (8x for the full enclosure)

- 2x M2x8mm screws

- 2x M4x15mm screws

- 2x M4 nuts

Tools

- M2, M3, M4 allen wrenches

- Philips/flathead screwdriver

- Glue gun

- Heat inserter and/or Soldering iron

- Optional: wrench/needle nose pliers

Like always, .step and all other files will be provided on this project’s Github Page so you can print and create your own!

Disclaimer

This project involves some up close work with contained, isolated power supplies. Additionally, this project is plugged into mains voltage, increasing the risk of electrocution. If you are not entirely comfortable or experienced with this kind of project and it’s associated risks, please do not attempt this build.

The Build

This project is centered around two components: A laptop power supply, and an adjustable DC-DC buck converter.

Component Explanation

- The laptop power supply accepts the 120-volt alternating current (AC) exiting the outlets in your house, and provides a stable, direct current (DC) output to power your laptop and it’s battery. In my case, I am using a 65 watt power supply that outputs 20 volts at up to 3.25 amps.

- The adjustable DC-DC buck converter is a component that accepts a DC voltage between 4V - 38V, and yields a 1.25V - 36V output. This output can be adjusted using a potentiometer, which is how I made my power supply produce more than a single voltage. However, an important consideration for this component is that the output voltage can never exceed the input voltage.

I chose to use a laptop power supply instead of an ATX or similar power supply for two reasons:

- Laptop power supplies come in much smaller form factors, as they are designed to be portable and carried around with a laptop. In my case, portability was not a high concern, but size was.

- Laptop power supplies have a single output, generally a DC connector or a USB-C interface, which is easy to find connectors for. ATX power supplies terminate in a variety of ways, including 4-pin Molex, PCIE, and SATA connectors, which are more difficult to directly interface with.

The first step of this project involved laying out the schematics for the electrical components. Creating a schematic before building your projects vastly increases the chances of success, which I learned firsthand during this project. In fact, this blog post is detailing the second attempt I made to complete this project; my first attempt used an ATX power supply salvaged from an ancient desktop PC, and ended in failure when I got totally lost in the mess of wires I had made for myself.

Additionally, my original design called for a number of extra features I scrapped in my second version in favor of stability and simplicity. I had designed my original desktop power supply to supply a range of fixed voltages (3.3v, 5v, 12v, -12v) as well as a variable voltage output. However, to simplify my design I opted for a single variable voltage output on my final design.

Design Interface

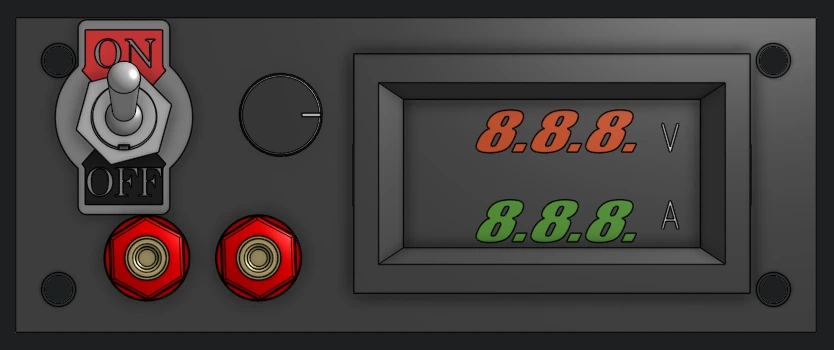

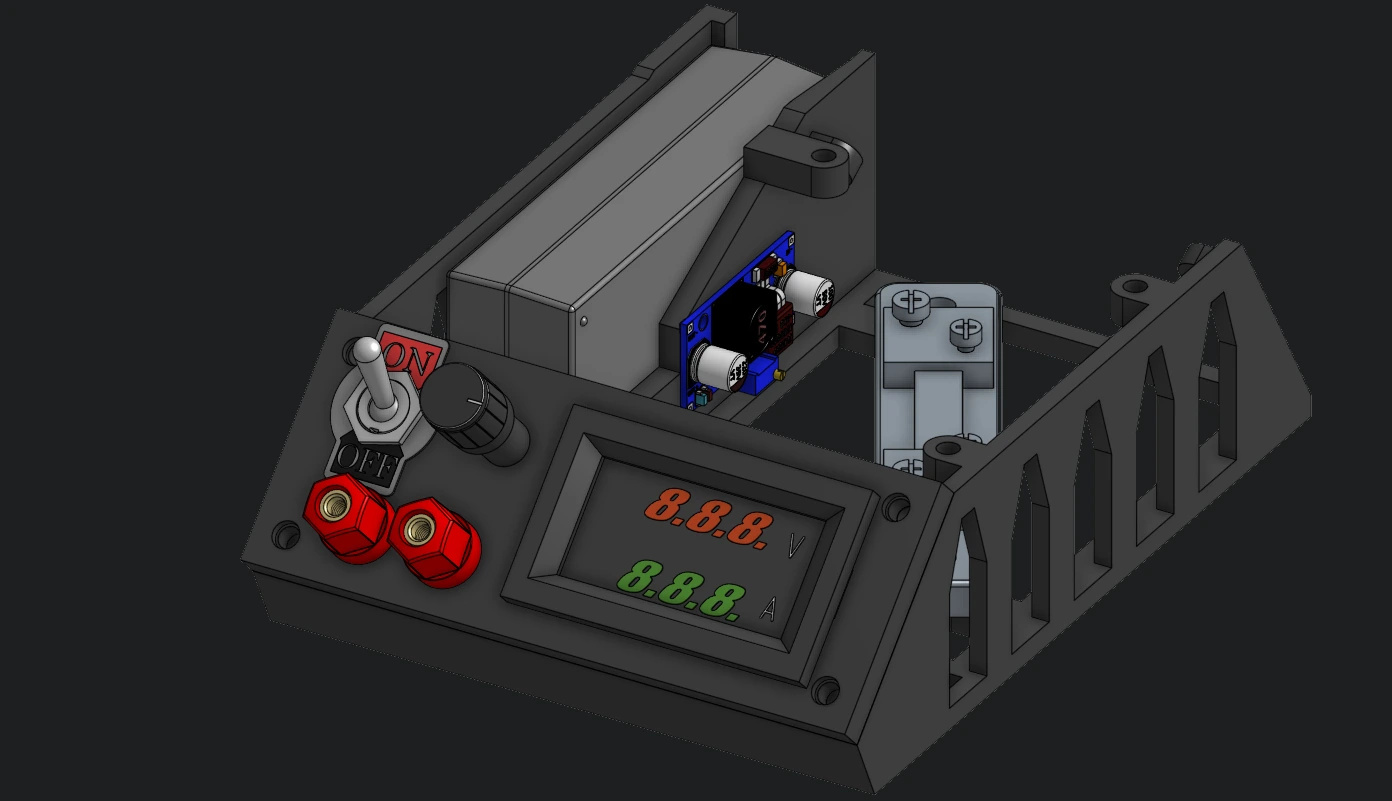

The interface that I settled on was simple: two banana plugs for power and ground, a dial to adjust voltage, a volt/amp meter, and a power switch. In the end, the front panel looked like this:

The front panel doesn’t mean anything, however, if it doesn’t work with the electronics behind it. So, behind the front panel, I needed to implement the following features:

- A space to hold the laptop power supply, ensuring that the AC plug is easily accessible from the back

- A mounting region for the DC-DC Buck converter, with adequate airflow for the switching circuitry

- A mounting region for the current shunt resistor. If you aren’t familiar, a current shunt resistor is a component with a known resistance connected in parallel with an ammeter, which is use to calculate the amperage of a circuit through the voltage drop across the shunt. Essentially, it’s an additional required component to enable the ammeter to function properly.

Actually building it

The first step in actually building the power supply was to connect the laptop power supply to the DC-DC buck converter. The laptop power supply did not terminate in a USB-C connector, however; it terminated in Lenovo’s proprietary DC connector.

The first step in actually building the power supply was to connect the laptop power supply to the DC-DC buck converter. The laptop power supply did not terminate in a USB-C connector, however; it terminated in Lenovo’s proprietary DC connector.

Thankfully, since I salvaged this power supply from an old, broken Lenovo laptop (the C740-15IML model), I also had taken apart the laptop itself and removed the corresponding DC connector, so I could continue on with the project. The DC connector had 5 wires leading out of it:

- 2 positive wires

- 2 negative wires

- 1 grounding wire

I soldered the DC connector’s positive and negative leads to the input +/- pins on the DC-DC converter, and folded the grounding wire back so that it doesn’t short any other connections. Ideally there would be another place for me to ground the wire, but since this power supply isn’t designed for high-current applications, grounding isn’t essential.

Next, I soldered the new potentiometer to the DC-DC converter’s potentionmeter pins. The module comes with a built-in trimpot, but those aren’t particularly practical for quickly adjusting voltage. So, I instead opted to use a 10kΩ rotary potentiometer in lieu of the included trimpot. So, a quick replacement job later, and the power supply is technically functional! However, it doesn’t have a functional connector, volt/ammeter, or an off switch, so I set out to add those next.

First, I soldered a wire to the ground output terminal of the DC-DC converter, leading into one terminal of the ON/OFF switch that I selected for this project. It is rated for much more current than this project will ever create, but I selected it mainly for the aesthetics and the intuitive design.

Next, I led a wire out of the other terminal of the power switch to one end of the current shunt connector. Then, across the shunt I screwed in a second wire leading to the black banana connector designated for ground. Then, I screwed in a second wire leading out of the first end of the current shunt connected to the COM terminal of the power meter. Third, I screwed in a wire to the second end of the current shunt, leading to the A+ terminal (Current Input) of the power meter. Finally, I soldered two wires to the positive end of the DC-DC converter. One of them led to the red banana connector designated for ground, and the other led to the V+ (Voltage Input) terminal on the power meter.

With the wiring complete, the last thing to do was to mount everything and test it. I went through a few more iterations of the front panel geometry before I was able to settle on something that had the proper tolerances for my components. I learned A LOT about 3D printed tolerances over the multiple revisions I had to make to this panel (As a general rule of thumb, I add a tolerance of +0.4mm to whatever value I measure to ensure a firm, but not overly-tight press fit.) After those revisions, I happily pressed each component into the front panel, screwed the panel into the chassis, and powered it on for the first time.

Conclusion

Since the first time I flipped the switch on my DIY desktop power supply, it has become my single most used DIY project to date. I have used it to inject voltage into various projects, ranging from Arduinos, ESP32s, Raspberry Pis, and even older SBCs, like the UDOO Quad (Look out for a blog post on a project involving this SBC soon!), or even the ancient MIT Handy Board. This was one of my earliest projects as well, and I have learned so much since then.

What I would change

- In the second half of the potentiometer’s travel, the voltage doesn’t increase any further. This is most likely due to my initial power supply not supplying the full 38v that the DC converter can take. Thankfully I haven’t run into any cases where I need to inject voltage greater than 20v, but that is a feature available on most desktop power supplies you can purchase online.

- The design for the case is not ideal. I had just gotten a new 3D printer, and I was truly a novice at designing 3D models that could be easily printed. As such, I prioritized reducing filament usage so much that I had to use a ton of supports just to print it, defeating the whole purpose. If I could go back, I would definitely redesign the case to be more compact and fully enclosed (since at the moment, I haven’t even printed a lid for my supply.)

- Wires are everywhere in this build. The internals of the power supply are the very definition of spaghetti wiring, and I would 100% design a circuit board to keep the sensing signals neat and tidy. My supply is surprisingly robust as it is though, and the price of a custom circuit board would most likely outweigh the price of a genuine desktop power supply, so that doesn’t seem like a likely follow-up project in the near future.

- When I originally made this project (in December 2023), I was unfamiliar with the concept of threaded inserts. This led me to create holes in my print for small machine screws to cut into to hold the DC-DC buck converter in place. Interestingly, I did use heated inserts for attaching the front panel to the chassis, but I didn’t consider using them to mount the buck converter, so I’d definitely redesign the chassis to fit the converter without relying on screws to carve through the plastic.

- When I was creating the wiring for this project, I made a bit of a mistake. It wasn’t anything that impacted the effectiveness of the power supply, but it probably has a small impact on efficiency and longevity. See, I wired the power switch after the DC-DC converter. At the time I didn’t realize my mistake, but after my first power-on, I saw it clear as day: the indicator LED on the buck converter stayed on, even when the power supply was dormant. This is because the laptop power supply is still providing a trickle of current to power the LED, even though the buck converter circuitry is inactive. Fixing this would have been trivial (just place the switch between the laptop power supply and the DC-DC buck converter), but the short leads on the female DC plug made it impractical to do so, and so I simply forgot to wire it properly.

Even with all of these drawbacks, they are miniscule compared to how helpful this project has been for me. Recently, even after over a year of using this build for almost every subsequent project, I finally figured out how to calibrate the voltmeter and ammeter! One of my biggest qualms with my design was that the ammeter was wildly inaccurate, but now its usually only about ~100mA off of the result I can obtain with my multimeter. An underrated part of this project is the DIY banana plug-to-crocodile clips that I made soon afterwards to let me take full advantage of the design, and they have served me well through being dropped, throwing sparks, and the occasional short to ground; I’m not perfect. Overall, I have found this project to be my most useful DIY device I have ever built, and I think its an essential tool for any aspiring electrical, electronics, or computer engineer that wants to get experimenting with circuits young, like I did. Thank you so much for reading.